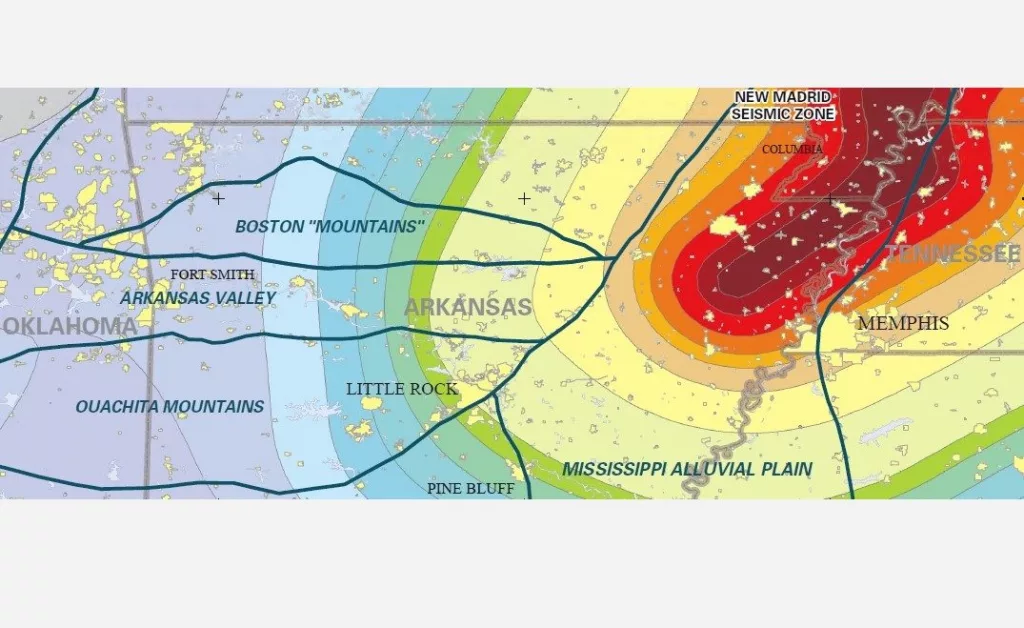

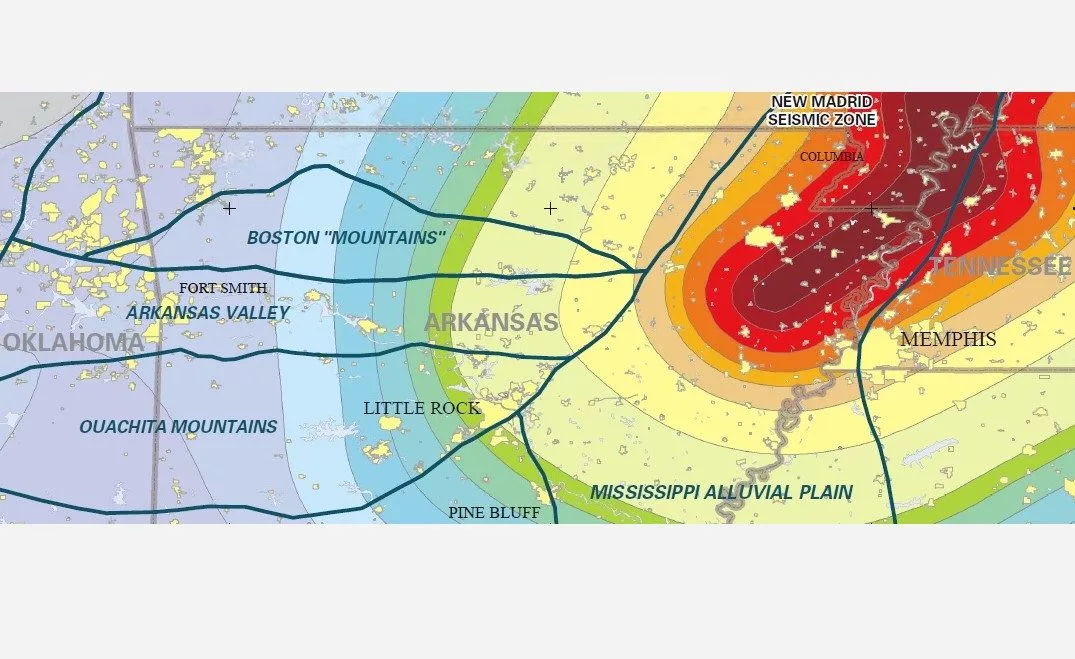

An illustration showing the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The red portion indicates the highest probability of devastating earthquakes. (Arkansas Geologic Survey)

State public safety officials maintain awareness and education programs

By Kenneth Heard, Arkansas Advocate

Former Mississippi County Office of Emergency Management director David Lendennie was in his bathroom early on the morning of Aug. 22, 2008, when the ground shook beneath his Blytheville home.

A 3.7-magnitude earthquake had rumbled along the southern end of the New Madrid Seismic Zone. Pictures rattled on walls, older concrete and brick foundations cracked, and startled residents were shaken up. There were no injuries.

Lendennie, who passed away in 2021, would tell of his predicament when discussing that quake to prove a point. You never know when an earthquake can strike on the most volatile and dangerous fault system in the country. Being prepared for catastrophe is essential, he said.

It’s easy to get complacent, safety officials say, because earthquakes cannot be predicted; there are no warnings like when inclement weather approaches.

On average, the New Madrid Seismic Zone records 10 times more earthquakes in a year than tornadoes, for example. Arkansas experiences 30 to 40 tornadoes on average annually compared to the New Madrid zone’s average of 250 to 300 quakes, many of those in northeast Arkansas. Only a handful of quakes large enough to be felt have occurred over the past decade in Arkansas. That, officials add, helps build the general complacency.

Still, the U.S. Geological Society predicts that there’s a 25% to 40% chance of a 6.0-magnitude earthquake along the seismic zone within the next 50 years. They’ve been using that percentage for the past 20 years, but Arkansas stage geologist Scott Ausbrooks said the society has not increased the potential due to the passage of time yet since the first prediction.

“It’s not if, but when,” Ausbrooks said of the possibility of a large temblor in the area.

The New Madrid Seismic Zone extends from Marked Tree, Arkansas, north through the Missouri Bootheel. One fault shoots across Missouri and into northwest Tennessee and another runs north toward southern Indiana.

Most of the earthquakes rumbling along the fault system range between 1.0 and 2.0 in magnitude and go unfelt. But on occasion, a larger earthquake will occur, briefly reminding people of the danger of the area.

A 6.0-magnitude quake would cause “quite a bit of damage,” said Hilda Booth, the earthquake program manager for the Arkansas Department of Public Safety’s Division of Emergency Management.

“Cell phone towers would come down,” she said. “Roads could be destroyed. Older buildings could collapse. Electricity would be knocked out.”

The state’s emergency department constantly puts out messages about earthquake safety. Homeowners are advised to strap down their hot water heaters and to ensure heavy furnishings like book cases are secured and won’t topple during earthquakes.

Iben Browning’s prediction

Occasionally, quake scares do arise. In the fall of 1990, New Mexico climatologist Iben Browning predicted a major earthquake near New Madrid, Missouri, would devastate the area in the first week of December.

Browning had correctly “predicted” the September 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that disrupted the World Series in San Francisco and killed 63 people, 42 of them in the collapse of a double-deck freeway. Browning consequently gained national media attention; so his prediction for a large New Madrid quake gained some credibility.

Schools closed that December. As people flocked to Walmart to buy batteries, generators, water and other emergency supplies, media outlets flocked to New Madrid to wait for the shaking.

But the earth remained still and thoughts of the earthquake potential subsided.

Because of the delta alluvial soil here, earthquake energy is more apt to travel much farther, Ausbrooks said, than those in the rocky California area.

“Every so often, we’ll get an earthquake [in the seismic zone], and people will get excited again,” said Lacey Kanipe, the public information officer for the state’s department of safety.

“Once they realize that we can have earthquakes here, peoples’ interest increases and they want to get involved,” she said.

On Dec. 10, 2024, seven earthquakes were recorded in southeast Missouri within a 9-hour period. One measured 3.0 in magnitude and was felt in Missouri, Tennessee and Arkansas.

New Madrid quake history

The seismic zone is best known for three major earthquakes that blasted the region during the winter of 1811 and 1812.

The first quake struck in the early hours of Dec. 16, 1811, along the Cottonwood Grove Fault in northeast Arkansas. Because there were no recording devices to measure earthquake intensity then and there was only a sparse rural population that experienced the violent shaking, geologists aren’t sure how intense the quake was. Scientists estimate it ranged around 7.7 in magnitude and was followed by three aftershocks measuring around 6.0 in magnitude or greater.

A woodcut illustration of the New Madrid earthquake of 1811. (Public domain image)

A woodcut illustration of the New Madrid earthquake of 1811. (Public domain image)

A second quake happened on Jan. 23, 1812, near New Madrid and was estimated to range between 6.8 and 7.8 in magnitude. It was followed by a third major earthquake on Feb. 7, 1812, east of Reelfoot Lake, Tennessee, and measured between 7.5 and 7.8 in magnitude.

Witnesses at the time reported seeing “waves” in the soil as the earth moved. Because of the delta alluvial soil here, earthquake energy is more apt to travel much farther, Ausbrooks said, than those in the rocky California area.

The 1811-1821 quakes were also so intense they created a phenomenon known as “liquefaction,” or the compressing of underground soil so strongly that they shoot out as geysers of sand and liquid. Liquefaction is still evident today. A flight over farmland in Crittenden and Mississippi counties will reveal large blotches of sand amid the darker, more fertile soils.

Archeologists have found evidence of liquefaction from earlier eras, indicating that major quakes rattled the area in the distant past.

The science that causes quakes on the New Madrid Seismic Zone is relatively unknown when compared to those along the western coast of the United States.

There on the western edge of the continent, tectonic plates shift and create friction and stress that’s released suddenly on fault systems like the famed Sam Andreas.

The New Madrid faults are hidden under thick layers of river sediment and are considered midcontinent rifts. Tremors are caused more by plates compressing together and lifting together.

Scientists have proposed the quakes on the New Madrid are the results pressure from the eastern and western halves of the continent pushing together.

‘People need to be ready’

The New Madrid Historical Museum, located on New Madrid’s Main Street, is one of a few spots that serve as a constant reminder of the potential for more quakes.

A section of the museum is dedicated to the large 1811-1812 quakes and includes tips on surviving earthquakes.

The museum sees about 5,000 visitors a year, and 80% come to see the earthquake display, said director Jeff Grunwald.

“We have a Civil War exhibit from an 1862 battle here, and we have a lot of Mississippian-era pottery,” Grunwald said. “But the driving force for coming here is the earthquakes.”

Grunwald has felt several earthquakes since moving to southeastern Missouri 12 years ago from Memphis.

“We may feel one every month or two,” he said. “A lot of times, it sounds like thunderclaps and the house shakes.

“There is awareness for earthquake potential with people here,” he said. “It is continually looked at. We do have a lot of reminders.”

Booth and other state emergency officials travel to Arkansas schools to educate youngsters about disaster preparedness. February is considered Earthquake Safety Month. Booth will post tips on social media, encouraging residents to develop emergency kits, secure heavy furniture and hot water heaters and other ideas.

“We want to keep the awareness in the limelight,” she said.

Officials are also constantly assessing area buildings to determine if they can withstand the earth’s shaking and be used as emergency shelters. They will also inspect highways, interstates and access roads for use for rescue vehicles.

“People need to be ready,” Ausbrooks said. “This area doesn’t look like what you’d expect earthquake country to look like. You don’t have the mountains like in California or the valleys in Utah. It’s all under the Delta soil here.

“Earthquakes can happen anywhere,” he said. “We don’t know where faults are until they are active. There’s no warning. They just happen.”

The Arkansas Advocate is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization dedicated to tough, fair daily reporting and investigative journalism that holds public officials accountable and focuses on the relationship between the lives of Arkansans and public policy.

Have a news tip or event to promote? Email White River Now at news@whiterivernow.com. Be sure to like and follow us on Facebook and Twitter. And don’t forget to download the White River Now mobile app from the Google Play Store or the Apple App Store.

Get up-to-date local and regional news/weather every weekday morning and afternoon from the First Community Bank Newsroom on Arkansas 103.3 KWOZ. White River Now updates are also aired weekday mornings on 93 KZLE, Outlaw 106.5, and Your FM 99.5. And catch CBS News around the top of the hour on 1340 KBTA.